Rachel Breen is an artist who finds some of her most profound inspiration in events that either happened long before she was born or in places halfway around the world from where she lives.

Breen, who lives in Minneapolis and has been a professor of art at Anoka-Ramsey Community College for almost 25 years, prefers to work with the medium of clothing and with a sewing machine as the instrument of her designs.

As a descendent of Jewish immigrants, she grew up familiar with the story of the Triangle Shirtwaist Factory fire that caused the deaths of 146 people – including 123 who were teen girls and young women, most of them Italian or Jewish – in 1911 in New York City. It remains one of the deadliest industrial disasters in U.S. history.

More than 100 years later, and well after Breen earned her Master’s of Fine Art at the University of Minnesota and launched her career, she was shocked at the historical echo of the Rana Plaza collapse, when a structural failure of a building in Bangladesh killed more than 1,100 people – most of them garment workers – in 2013.

“How could this happen after we learned and put so many safeguards into place in this country after the Triangle Shirtwaist fire and then something similar happens a century later where there’s another even worse tragedy around people who are just trying to make their lives a little better by making clothes?” Breen asked. “That sent me on a path to research and it’s what my work has been about ever since.”

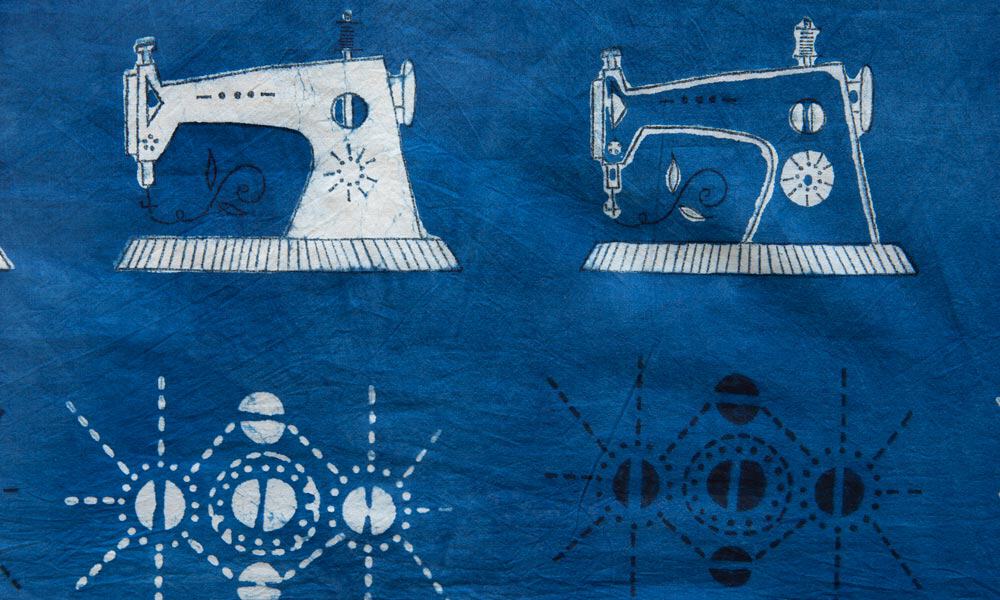

She has participated in more than 50 solo and group exhibitions, collaborative projects and public engagements in the past decade, the latest of which opens Tuesday (October 24) in the Alice R. Rogers and Target Galleries at the Saint John’s Art Center. Her material art exhibition titled “At the Root: Materials and Power” will feature approximately a dozen different pieces created from used textiles that examine the relationship between labor conditions under which clothes are made and its relation to overconsumption. She also will unveil a wall drawing that students from the College of Saint Benedict and Saint John’s University will help her create, using a sewing machine without thread as a drawing tool.

Breen will appear at a reception from 5-7 p.m. November 2nd, during which she will give an artist talk at 6. She also will work with Andrea Shaker of the art department faculty to visit a class and conduct workshops open to students, faculty and the public. Breen’s exhibition will continue through December 9th.

Above is an example of how Rachel Breen works in the medium of used clothing.

Used clothing as a medium

Breen works almost exclusively with used clothing. She disassembles items to reveal how they’re made and then reassembles them in complex ways. Some of her pieces are what she calls “collective garments,” which could be worn by a group of as many as 10 people.

“What does it mean for 10 people to have to wear a piece of clothing together?” she asked. “You have to move carefully, and you have to communicate so you don’t rip it. That’s a metaphor for what I think needs to happen in terms of social change. And I think about the stitch as a symbol of our interdependence with other people. A stitch is next to our skin and 99 percent of the people in this world wear clothes made on a sewing machine. I find that fascinating and it represents our commonality.”

Her goal is to provoke conversation about the intersection of workers’ rights and climate change.

“They are connected, absolutely,” Breen said. “I want people to think, ‘What do we do? What can be done?’ That serves as a call to action.”

She said mass creation of clothing is a lot more complicated than just going to a store and buying an item that says, “Made in Bangladesh.” The cotton in that clothing may have been grown in Texas and shipped to China to be woven. The resulting fabric is sent to another part of China to be dyed before it arrives in Bangladesh to be cut and sewed. The clothes then might go to a warehouse in Abu Dhabi before they arrive at a warehouse in Florida, where they’re loaded on a truck and driven to the store in Minnesota.

“The climate impact just of the transportation of the materials is immense, not to mention the pesticides that help grow the cotton and toxic chemicals involved in the dye and the machines that power all these locations and the fact that the workers are treated horribly,” Breen said. “They’re doing repetitive tasks and working 10-12 hours a day on an assembly line.”

Rachel Breen with her artist’s tool of choice.

Perspective from India, U.S. labor history

She knows as much, as well as some potential solutions, following her experience as a Fulbright Scholar in India. She spent five months there last year, looking at clothing practices. And, during a sabbatical in 2021, she visited the Kheel Center, a labor archive at Cornell University, where she delved into events like the 1912 Bread and Roses Strike in Lawrence, Massachusetts, and learned about the history of the International Ladies Garment Workers Union. One of her creations that will be on display at SJU is called “Banner for the Commons,” which was inspired by that research and is an homage to huge banners made at the founding of the ILGWU in 1900. Despite the name, workers in other parts of the world often have no union representation.

“How do we show that we’re connected to these people on the other side of the planet who are hugely harmed by our shopping and consumption behaviors and all the ways we use materials in our country?” Breen asked. “We consume more per person, and our carbon impact per person is much greater. That doesn’t seem fair. Acknowledging our place in that relationship is part of signifying that we care, we see ourselves as part of a global community and that we could even start having conversations about change.

“Initially, when people would see my work, they’d ask, ‘What can I do? Tell me where I should shop?’” Breen added. “I thought that was such an interesting and surprising response – as though just shopping at a different store could solve this problem. To me, that represents a lot of what’s wrong with our culture right now. We don’t understand how change happens and we think we can do it just by shopping at one place or another. It’s much more complex than that and change really only happens when we work collectively together.”

She encourages people to realize that perhaps 20% of used clothing is resold. Much of the rest winds up in a third-world Global South landfill.

“Buy less, buy better,” Breen said. “You can spend more on quality. That’s part of the solution. But I don’t propose to have all the answers because these are large problems. I hope to provoke questions and encourage reflection. For change to happen, we have to care.”

One of Rachel Breen’s creations that will be on display at SJU is called “Banner for the Commons,” which was inspired by research into the founding of the International Ladies Garment Workers Union in 1900. Despite the name, workers in other parts of the world often have no union representation.

This is a close up of the detail in the Banner of Commons.

Rachel Breen has been an art professor at Anoka-Ramsey Community College for more than 25 years.

Above is a detail of the stitches Rachel Breen used in one of the pieces she will have on display.